The first thing to note from the article is the rather ugly and shameful bias that it displays. The unabashed and continuous praising of both Braid and Jonathon Blow is one of the worst examples of journalism I've seen in some time. Journalists should be presenting a balanced view of their subject matter, because to do otherwise effectively turns their work into a big long opinion piece. That's not journalism. That's a blog post or at best and editorial column.

Part of the problem is that Braid is held up as a shining example of what games should be, and all other games are denigrated as meaningless and puerile entertainment fit only for idiots and juveniles. To dismiss something as having no real merit in an entertainment form simply because it does not meet one particular standard - in this case "being artistic" - belies the inherent benefit of diversity within a medium. If all games must be artistic in order to have worth, then the same logic must also be applied to movies, books, music, theatre and any other medium that can be used to communicate an idea to an audience. This issue is exacerbated by the shameless cherry picking of arguably the most artistically shallow counter-examples in order to attempt to prove this point. By picking games focused entirely on action and killing/shooting/fighting, Clark demonstrates an even worse bias than his continual praise of Braid. By failing to acknowledge even a single other game with depth in terms of storytelling, drama, theme or literary ideas, the argument comes across as completely and utterly uninformed.

Dear Esther, anyone?

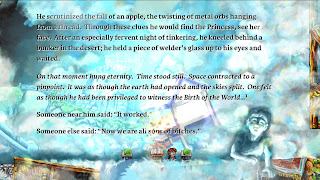

For those who don't know (seriously, you should play it, but this is your last chance) Braid is a 2D platformer about the story of Tim. The game appears to be about Tim attempting to save the princess, as he travels through a series of levels fronted by narrative describing his attempts to find and reconcile his search for her. The game features some interesting time rewinding mechanics, which lead the player to solving puzzles in some fairly unique ways for a platformer. It has some well designed and thought out mechanics.

I enjoyed Braid quite a lot, but as I was playing, something always felt a little off. There was some element of me that felt that the story wasn't quite right. The disjointed narrative wasn't confusing, but intriguing, both from a experiential and writing perspective. I found the writing to be missing an element of personalised emotion, as though the writer were taking ideas that they conceptually understood at a factual level, but did not emotionally comprehend the ramifications of the content. To me, it was as though it had been written by someone with autism or asperger's syndrome. This didn't make the game any less interesting, but meant as a player I was trying to insert real emotion into Tim's story because it only contained only the idea of emotion rather than emotion itself.

The real disconnect came for me when I reached the game's epilogue, where it is revealed that "The Princess" referenced throughout the game is actually the atomic bomb, and that the game is seemingly about Tim's attempt to reconcile and repent for his role in The Manhattan Project. The disconnect wasn't the reveal itself, because it was always obvious that there was something more to the story, but the issue was instead with the manner in which the reveal was done. The revelation was delivered in an overly heavy-handed manner that shoved it down the player's throat. Up until this point, the game had been filled with allegory and intentionally vague writing, which was undone by explicitly naming the princess and issuing quotes from people involved in The Manhattan Project. By making the twist and overall story so patently obvious, Braid undid much of intrigue and interest that it had sparked up until that point.

This isn't mature story telling

The ending to Braid was a disappointment because it could have been so much more. Maturity in atorytelling is not achieved through heavy handed delivery that verges on breaking the fourth-wall. The abrupt directness of Braid's reveal is a hallmark of immature storytelling, almost explicitly explaining the whole purpose of the game. Instead of providing evidence for the player to deduce the ending on their own, Braid comes out and directly states the truth of the game's mystery. Great themes and ideas should be present via the entire delivery of the work, rather than directly stated through a twist right at the end.

For me, one disappointment was that an alternate scene does exist that would have gone some way to providing a meaningful ending without this heavy handed approach. If the player obtains a series of stars in the game (all of which are very obscure and difficult to obtain), it is possible for them to (again, through an obscure process) actually touch the princess as part of the game. This does not occur as part of normal gameplay. Upon doing so, the screen flashes white and an explosion noise sounds. When the white fades away, the Princess is gone. In the context of having already seen the heavy handed ending, this series of events makes complete sense, but devoid of it, it is a strange occurrence that is obviously symbolic, though it would be up to the player to determine its significance. At this point, the game could have simply forced the player to rewind in order to proceed, just as it does in the "normal" ending, and none of the symbolism of that ending would have been lost.

Conversely, Blow has directed much criticism at Red Dead Redemption, for being about a father figure attempting to obtain redemption, but in attempting to do so, the player must murder hundreds of people during the course of the game. Blow's argument is that the murder undermines the portrayal of the lead character of John Marsden. The unfortunate thing here is that Blow has missed the entire point of the storytelling and the game's climax. It's true that Marsden kills repeatedly during the adventure despite being cast as a "good" character, but the tale ultimately describes how he is unable to escape the burden of his past as a criminal. That Blow fails to understand this is slightly ironic, given that this idea has strong parallels with his own story within Braid. Moreover, it fails to see the larger picture that is delivered in the game's climax.

John Marston isn't meant to be "good"

After many hours of tribulations working for the Government in order to bring his former criminal friends to justice, Marston is finally set free and allowed to return to his home. This is not without a great deal of argument with his employers, who have repeatedly demonstrated their unwillingness to let Marston go, and forced him to do more than they initially asked. Marston returns to normal life with his family and the player herds cattle, delivers supplies, teaches his son how to hunt and otherwise lives a normal life. This is undone in the final mission of the game, where Government troops come for Marston. Sending his wife and son off to safety, Marston barges out of the barn and attempts to take down the Government troops, but after the player empties their weapon, the game removes control and shows Marston dying in a hail of bullets. The game jumps your control to that of his wife and son riding away on a horse, who hear the gunfire. You yhen ride back to the farm to find John Marston dead.

Red Dead Redemption in this sequence tells the player through its actions, gameplay and visuals that there are some debts that may never be paid off without paying the ultimate sacrifice. Marston has spent the entire game trying to escape his old life by effectively reliving it, which is ultimately a futile endeavour. Despite a game spent searching for redemption through murder, Marston only eventually finds redemption for his misdeeds by sacrificing himself to save the lives of his family. The game did not feel the need to have a voice over to explicitly tell the player this or otherwise deliver this message in a heavy handed manner, because it was more mature than that. What the writers at Rockstar recognised that Blow did not is that by allowing the player to interpret the meaning of their work rather than being explicitly told the meaning, their storytelling was inherently more meaningful and mature.

Playing your cards close to your chest usually works better

All analysis aside, perhaps the most stupid thing is the necessity that some people seem to have to insist that games must be "artistic". For starters, no one can define what is meant by "artistic". What some people consider to be "art" is not by others, and the same goes for things considered to be "artistic". What is worse is that this train of thought stems from a viewpoint that games are somehow an inferior storytelling medium or entertainment form. It is as though unless video games can be considered art by some arbitrary measure, that they are somehow a childish pursuit or lesser creations. There seems to be an insistence on claiming that video games are dumb, even when this is often because people make them so by analysing them at only the most perfunctory level.

Attempts to be deliberately artistic, which is largely Braid's modus operandi, are not necessary to prove the maturity of games. If anything, this approach smacks of a pretentious attempt to be sophisticated rather than simply being sophisticated. Simply put, Braid is one of a number of games that are trying too hard. Nevertheless, Braid still (mostly) succeeds at being intelligent and thought provoking, but that is in spite of its blatant attempts to be "artistic" rather than because of it.

Games do not need to deliberately attempt to be artistic. Games can be artistic by their very nature. Every time a player stops to admire a beautiful virtual landscape, a game is artistic. Every time someone stops to consider their actions and consequences before acting, a game is artistic. Every time a discussion is held about the "real meaning" of events, scenes or dialogue in a game, that game is artistic. Every time a game inspires emotion in a player or even those people watching it, a game is artistic. To deny otherwise would be to deny the integrity of any other artistic medium. If someone wants to denigrate games as a medium lacking merit, then they simply don't understand them. For gamers or game designers to carry around a chip on their shoulder and take every opportunity to insist and showcase "how artistic they are" is a path that will lead to pretentiously vapid games, more obsessed with being art than actually being art, or a game, or an interesting storytelling medium.

I actually just finished RDR this week and loved the final act. You know that the foreshadowed betrayal is coming ("Not all of the old gang..." etc) but the return to normality and how earnestly John applies himself to regain his family's trust is a wonderfully played series of missions.

ReplyDeleteThe coda, with Jack tracing Edgar Ross was wonderful too and a great moment of catharsis as the antagonist is finally defeated a generation later. I can't wait to spend a bit more time with him and wrap up the last of the unfinished business.

Also, it's been ages since I followed/commented as Google Reader had decided to randomly unsubscribe from this feed.

Yeah, totally agree. There was sufficient foreshadowing that you felt something had to come. Even so, I was a bit shocked to get gunned down at the end, but marveled at it at the same time. Agreed that Jack's showdown with Edgar Ross was also brilliant.

ReplyDeleteIn terms of Rockstar's storytelling, they really outdid themselves (and many others) with RDR. To me, anyone decrying that it's filled with poor writing, or a shallow example of storytelling or inconsistent because of the gameplay has truly missed the point.

I also thought that the final moments of John Marston were nicely crafted too - striding out of the door and into certain death, but determined to take some of them with you, it was the only way that character could have come to an end.

ReplyDelete