Today's post is an announcement for The Shattered War!

There's a new high resolution (720p) teaser trailer out to whet your appetite for the adventures in store for all players. I've set this post to display in a resolution of 480p by default, but please increase it to 720p if you want the best possible view!

Enjoy and spread the word!

Monday, September 26, 2011

The Shattered War: Teaser Trailer

Labels:

Dragon Age,

Modding,

Previews,

The Shattered War,

Video

Hacking minigames

A well executed mini-game is a great way to break up the gameplay patterns and introduce variety into a game for a player. If done well, it can add to the player's immersion and offer an additional small set of mechanics or strategies to master to complement the overall game. However, a mini-game that stylistically and aesthetically matches the overall tone of the game and the theme of the mini-game itself is excellent.

To that end, let's quickly analyse a few "hacking" minigames across different titles. While hacking by necessity limits itself to titles involving technology, there is still a wide variety of games and mechanics that have been implemented by developers. In a break from my normal tradition on analysing game design, I'm going to grade each out of 5 on three elements:

Style - How much it matches the "theme" of hacking. Do the aesthetics and gameplay make it feel like the player is "hacking"?

Theme - How well does it match the overall theme and aesthetics of the game? Does it feel like a coherent part of the overall game?

Gameplay - How do the mechanics of the minigame play out? Does it provide the player the opportunity to break up regular gameplay and master a (set of) game mechanic(s)?

Some of the numbers I provide might be a little controversial, but I'm including them as my personal subjective measure of the success of various components.

BioShock

Here is a mini-game that demonstrates an superb connection with the overall aesthetics and style of the game. The pipemania style mini-game to connect the start node to the end node matches the water themes of the game with commendable skill, and provides an enjoyable (and arguably proven) game mechanic to keep people interested. Player upgrades to increase the skill with hacking augment the connectivity with the overall game without hindering the core gameplay of the minigame.

Its main weakness is that this immediately recognisable mechanic does little to ingratiate itself with the idea that the player is "hacking" a machine. The player is quite clearly playing a "connect the pipes" game rather than anything that has a clear connection with the idea of hacking a device. The other weakness in the gameplay of the minigame is because of how repetitious and tedious it eventually becomes. However, this is technically not a failing of the minigame itself, but a failing of the game for the number of times it makes you perform the hacking minigame.

Style: 1/5

Theme: 5/5

Gameplay: 5/5

Fallout 3

Fallout 3 gave us "mastermind" as a hacking game. If given a group of words, pick the correct password over a series of guesses, where the player is told the number of letters they have in the correct position after each guess.

Initially, this seemed like an excellent mechanic, but it did not take long for it to break down. While the presentation was quite good and help impart the feel of a broken civilisation with broken computer terminals, the construction of the minigame itself was shallow and quickly predictable. Players quickly learned how to approach the fairly simple problem and could almost guarantee success every single time. It had all the repetitiveness of BioShock's pipemania without the associated skill requirement or time limit.

Style: 2/5

Theme: 3/5

Gameplay: 1/5

Mass Effect 2

Mini-games are one of the weak aspects of the Mass Effect series, and ME2's hacking mini-game doesn't really do much to buck this trend. It's simple symbol matching exercise on a scrolling grid, with a time limit and "danger squares" that can hinder the player's progress.

Aesthetically and stylistically it matches the overall feel of Mass Effect 2 quite, and potentially gives the player a vague "hacking" feel. However, it's a fairly lacklustre mechanic on the whole. There is a small degree of skill in its execution, but nothing that feels terribly taxing or engaging. Admittedly it's better than the bypass mechanic or (yuck) planet scanning, but those really don't offer a lot of competition.

Style: 2/5

Theme: 3/5

Gameplay: 2/5

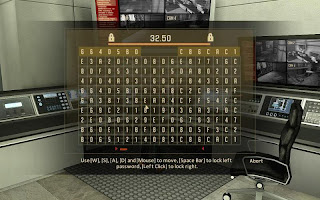

Alpha Protocol

Alpha Protocol presents the player with a large "find-a-word" where they must locate and "lock in" two sequences of characters within a large character grid within a time limit. The trick is that all the characters on the grid periodically change except for the two sequences within the grid. However, should the player take too long, these sequences can "relocate" once during the hack. The difficulty can be surprisingly deceptive, but it can be good challenge.

On a console, each thumbsticks controls the location of one of the two sequences; move the left thumbstick to move the left sequence, move the right thumbstick to move the right sequence. However, if you play on a PC, prepare to be infuriated by a poor control system using the keyboard and mouse, as the reaction of the controls is sluggish and can frequently result in an "incorrect lock-in", which results in a time penalty. This is one case where the PC is vastly inferior in its controls, and I'd deduct 1 (possibly 2) marks from the gameplay score because of this problem. Apart from this issue, this minigame matches both the overall tone of the game and imparts a good "hacking" motif.

Style: 3/5

Theme: 3/5

Gameplay: 4/5

Deus Ex

The aesthetics of the hacking in Deus Ex are superb, as it gives you what effectively appears to be a network layout. It is up to the player to analyse the best options to reach a target node (or multiple target nodes) in order to succeed at the hack. The unfortunate weakness of the system is the arbitrary nature of the gameplay due to the chance element of "detection". Every action within the minigame brings a risk of "detection" by the computer's security system, which immediately imposes a timelimit on the player's actions before they are detected and fail the hack. Nodes can be optionally captured that will assist the hack or provide external benefits to the player, forcing them to weigh up the pros and cons of risking "detection" against rewards like additional money or experience.

The problem with the detection mechanics is that it introduces the problem that there is no (or very little) player skill involved in the success or failure of the hack. Once the player is detected, the minigame degenerates into a click sequence that inevitably plays out exactly the same way each time. A hack can result in guaranteed failure if the player is detected upon their first action, whereas a retry could result in a straightforward success if the percentage chance of detection happens to go in the player's favour. There is an attempt to address this problem through the introduction of "stop worms" (which momentarily stall the detection countdown and hence player failure) or "nuke viruses" (which automatically capture a network node with chance of detection), not to mention player upgrades that increase the character's abilities which are necessary to hack "more secure" systems. Despite this integration that reinforce the concept of having to balance resources that runs through the entire game, these are still band-aid solutions that don't really solve the problem of an arbitrary difficulty.

Style: 5/5

Theme: 4/5

Gameplay: 2/5

While the appraisal of these different hacking mechanics might be an interesting enough topic in and of itself, I'm going to use it as a pre-cursor to a discussion about mini-game mechanics in general. That, however, will have to wait until another blog post...

To that end, let's quickly analyse a few "hacking" minigames across different titles. While hacking by necessity limits itself to titles involving technology, there is still a wide variety of games and mechanics that have been implemented by developers. In a break from my normal tradition on analysing game design, I'm going to grade each out of 5 on three elements:

Style - How much it matches the "theme" of hacking. Do the aesthetics and gameplay make it feel like the player is "hacking"?

Theme - How well does it match the overall theme and aesthetics of the game? Does it feel like a coherent part of the overall game?

Gameplay - How do the mechanics of the minigame play out? Does it provide the player the opportunity to break up regular gameplay and master a (set of) game mechanic(s)?

Some of the numbers I provide might be a little controversial, but I'm including them as my personal subjective measure of the success of various components.

BioShock

Here is a mini-game that demonstrates an superb connection with the overall aesthetics and style of the game. The pipemania style mini-game to connect the start node to the end node matches the water themes of the game with commendable skill, and provides an enjoyable (and arguably proven) game mechanic to keep people interested. Player upgrades to increase the skill with hacking augment the connectivity with the overall game without hindering the core gameplay of the minigame.

Its main weakness is that this immediately recognisable mechanic does little to ingratiate itself with the idea that the player is "hacking" a machine. The player is quite clearly playing a "connect the pipes" game rather than anything that has a clear connection with the idea of hacking a device. The other weakness in the gameplay of the minigame is because of how repetitious and tedious it eventually becomes. However, this is technically not a failing of the minigame itself, but a failing of the game for the number of times it makes you perform the hacking minigame.

Style: 1/5

Theme: 5/5

Gameplay: 5/5

Fallout 3

Fallout 3 gave us "mastermind" as a hacking game. If given a group of words, pick the correct password over a series of guesses, where the player is told the number of letters they have in the correct position after each guess.

Initially, this seemed like an excellent mechanic, but it did not take long for it to break down. While the presentation was quite good and help impart the feel of a broken civilisation with broken computer terminals, the construction of the minigame itself was shallow and quickly predictable. Players quickly learned how to approach the fairly simple problem and could almost guarantee success every single time. It had all the repetitiveness of BioShock's pipemania without the associated skill requirement or time limit.

Style: 2/5

Theme: 3/5

Gameplay: 1/5

Mass Effect 2

Mini-games are one of the weak aspects of the Mass Effect series, and ME2's hacking mini-game doesn't really do much to buck this trend. It's simple symbol matching exercise on a scrolling grid, with a time limit and "danger squares" that can hinder the player's progress.

Aesthetically and stylistically it matches the overall feel of Mass Effect 2 quite, and potentially gives the player a vague "hacking" feel. However, it's a fairly lacklustre mechanic on the whole. There is a small degree of skill in its execution, but nothing that feels terribly taxing or engaging. Admittedly it's better than the bypass mechanic or (yuck) planet scanning, but those really don't offer a lot of competition.

Style: 2/5

Theme: 3/5

Gameplay: 2/5

Alpha Protocol

Alpha Protocol presents the player with a large "find-a-word" where they must locate and "lock in" two sequences of characters within a large character grid within a time limit. The trick is that all the characters on the grid periodically change except for the two sequences within the grid. However, should the player take too long, these sequences can "relocate" once during the hack. The difficulty can be surprisingly deceptive, but it can be good challenge.

On a console, each thumbsticks controls the location of one of the two sequences; move the left thumbstick to move the left sequence, move the right thumbstick to move the right sequence. However, if you play on a PC, prepare to be infuriated by a poor control system using the keyboard and mouse, as the reaction of the controls is sluggish and can frequently result in an "incorrect lock-in", which results in a time penalty. This is one case where the PC is vastly inferior in its controls, and I'd deduct 1 (possibly 2) marks from the gameplay score because of this problem. Apart from this issue, this minigame matches both the overall tone of the game and imparts a good "hacking" motif.

Style: 3/5

Theme: 3/5

Gameplay: 4/5

Deus Ex

The aesthetics of the hacking in Deus Ex are superb, as it gives you what effectively appears to be a network layout. It is up to the player to analyse the best options to reach a target node (or multiple target nodes) in order to succeed at the hack. The unfortunate weakness of the system is the arbitrary nature of the gameplay due to the chance element of "detection". Every action within the minigame brings a risk of "detection" by the computer's security system, which immediately imposes a timelimit on the player's actions before they are detected and fail the hack. Nodes can be optionally captured that will assist the hack or provide external benefits to the player, forcing them to weigh up the pros and cons of risking "detection" against rewards like additional money or experience.

The problem with the detection mechanics is that it introduces the problem that there is no (or very little) player skill involved in the success or failure of the hack. Once the player is detected, the minigame degenerates into a click sequence that inevitably plays out exactly the same way each time. A hack can result in guaranteed failure if the player is detected upon their first action, whereas a retry could result in a straightforward success if the percentage chance of detection happens to go in the player's favour. There is an attempt to address this problem through the introduction of "stop worms" (which momentarily stall the detection countdown and hence player failure) or "nuke viruses" (which automatically capture a network node with chance of detection), not to mention player upgrades that increase the character's abilities which are necessary to hack "more secure" systems. Despite this integration that reinforce the concept of having to balance resources that runs through the entire game, these are still band-aid solutions that don't really solve the problem of an arbitrary difficulty.

Style: 5/5

Theme: 4/5

Gameplay: 2/5

While the appraisal of these different hacking mechanics might be an interesting enough topic in and of itself, I'm going to use it as a pre-cursor to a discussion about mini-game mechanics in general. That, however, will have to wait until another blog post...

Friday, September 9, 2011

Encourage players towards mastery

In my last post I talked about the game Darksiders and some of its shortcomings in relation to gameplay. One area that I thought the game was quite fun for the most part was in its fighting mechanics. As a beat-em-up game, it is mandatory that these mechanics be enjoyable. However, there is one significant deficiency in how the combat plays out that fails to capitalise on a potential means to improve it: the game does not provide incentives for players to master of the fighting mechanics.

The immediate and knee-jerk retort to this criticism is that the incentive is "not dying", which is accurate. However, this ignores the vast potential for improvement in the form of player-defined challenge. This is whereby players set themselves goals above and beyond what are enforced by the mechanics of the game itself. In stealth games, it may not just be to survive the level, it may be to do the entire level without being seen. Or it could to an entire level and to leave everything exactly how it was before the player entered - every door opened is shut, any light turned off is turned back on, any item (barring that which the player intends to steal) is returned to its rightful place. Other genres might see the player attempt a "no-reload" challenge, or a speedrun to finish the game in the shortest time possible, among many other possibilities.

These examples push the boundaries of what most players might do, and in the case of speed runs often "break" the normal mechanics of the game. However, the concept of providing players with self-governed challenge above that provided by the game is not only a great way to encourage players to replay a game, but also to improve their skill in the mechanics of the game. For an example, let's compare Batman: Arkham Asylum (B:AA) to Darksiders. In Darksiders, upon defeating an enemy, you claim "souls", typically blue souls, which represent the currency in the game used to buy items and upgrades. In B:AA, you gain experience from defeating enemies, which allows you to level-up and "buy" items and upgrades. The core difference is that B:AA actively rewards you based on how well you have mastered its combat system. Furthermore, it directly tells you what aspects of that combat system you have mastered.

These two games (as with many beat-em-ups) feature a "combo counter", keeping track of how many hit you've strung together in a sequence without missing or taking a blow. However, B:AA rewards the player who has a high maximum combo counter, using more challenging moves, and also for using a variety of different moves throughout the fight. It shows a separate message for each of these in an unobtrusive manner to show to the player how well they did in a particular fight. Furthermore, the "combat challenges" outside of the main story campaign push this concept even further, giving the player a points score based on their success, and allowing them to create a "leaderboard" of their scores and that of their friends.

Darksiders on the other hand does none of this. There is seemingly no benefit from generating large combos, and the game provides you no feedback about how well you are doing in combat besides the life meter of your character. It's not even clear whether "instant-kill" moves that the player can do offer any additional benefit aside from killing an enemy quicker than they otherwise might. It does incorporate fighting challenges into the main game, which offer additional souls based on your performance, but it never makes it clear exactly how much that bonus is - the player is merely left to guess how well they may or may not have done. These feel more like "training exercises" to teach the player particular basic mechanics and strategies rather than real "challenges". While this is appropriate given they are a mandatory part of the campaign, they lack the "challenge" of those in B:AA. Furthermore, they can't be repeated as individual challenges outside of the main campaign to allow the player to practice mastering a particular fighting technique or scenario.

B:AA encourages players to master its mechanics, to practice and learn to excel. This sort of encouragement results in greater player engagement, because while they can just "muddle through" with enough talent to get by, most players will want to achieve and gain the rewards that come from increased skill. The key is to tell players what they are doing right, and assign them a clear and tangible benefit from doing so. Simply saying "bonus" without saying why, or worse, invisibly rewarding the player, does not provide them with any incentive to "do well". Additionally, also make sure that this is done in an encouraging fashion. Don't penalise players for doing something wrong, but instead reward them for doing something right.

This encouragement will keep players coming back for more, make them want to improve their skills, master the mechanics of the game, and ultimately make them more engaged with the game - and an engaged and engrossed player is a happy player.

The immediate and knee-jerk retort to this criticism is that the incentive is "not dying", which is accurate. However, this ignores the vast potential for improvement in the form of player-defined challenge. This is whereby players set themselves goals above and beyond what are enforced by the mechanics of the game itself. In stealth games, it may not just be to survive the level, it may be to do the entire level without being seen. Or it could to an entire level and to leave everything exactly how it was before the player entered - every door opened is shut, any light turned off is turned back on, any item (barring that which the player intends to steal) is returned to its rightful place. Other genres might see the player attempt a "no-reload" challenge, or a speedrun to finish the game in the shortest time possible, among many other possibilities.

It's possible to finish Morrowind in under four and a half minutes

These examples push the boundaries of what most players might do, and in the case of speed runs often "break" the normal mechanics of the game. However, the concept of providing players with self-governed challenge above that provided by the game is not only a great way to encourage players to replay a game, but also to improve their skill in the mechanics of the game. For an example, let's compare Batman: Arkham Asylum (B:AA) to Darksiders. In Darksiders, upon defeating an enemy, you claim "souls", typically blue souls, which represent the currency in the game used to buy items and upgrades. In B:AA, you gain experience from defeating enemies, which allows you to level-up and "buy" items and upgrades. The core difference is that B:AA actively rewards you based on how well you have mastered its combat system. Furthermore, it directly tells you what aspects of that combat system you have mastered.

These two games (as with many beat-em-ups) feature a "combo counter", keeping track of how many hit you've strung together in a sequence without missing or taking a blow. However, B:AA rewards the player who has a high maximum combo counter, using more challenging moves, and also for using a variety of different moves throughout the fight. It shows a separate message for each of these in an unobtrusive manner to show to the player how well they did in a particular fight. Furthermore, the "combat challenges" outside of the main story campaign push this concept even further, giving the player a points score based on their success, and allowing them to create a "leaderboard" of their scores and that of their friends.

Darksiders on the other hand does none of this. There is seemingly no benefit from generating large combos, and the game provides you no feedback about how well you are doing in combat besides the life meter of your character. It's not even clear whether "instant-kill" moves that the player can do offer any additional benefit aside from killing an enemy quicker than they otherwise might. It does incorporate fighting challenges into the main game, which offer additional souls based on your performance, but it never makes it clear exactly how much that bonus is - the player is merely left to guess how well they may or may not have done. These feel more like "training exercises" to teach the player particular basic mechanics and strategies rather than real "challenges". While this is appropriate given they are a mandatory part of the campaign, they lack the "challenge" of those in B:AA. Furthermore, they can't be repeated as individual challenges outside of the main campaign to allow the player to practice mastering a particular fighting technique or scenario.

Do I instant-kill or not? I don't know; the game doesn't tell me!

B:AA encourages players to master its mechanics, to practice and learn to excel. This sort of encouragement results in greater player engagement, because while they can just "muddle through" with enough talent to get by, most players will want to achieve and gain the rewards that come from increased skill. The key is to tell players what they are doing right, and assign them a clear and tangible benefit from doing so. Simply saying "bonus" without saying why, or worse, invisibly rewarding the player, does not provide them with any incentive to "do well". Additionally, also make sure that this is done in an encouraging fashion. Don't penalise players for doing something wrong, but instead reward them for doing something right.

This encouragement will keep players coming back for more, make them want to improve their skills, master the mechanics of the game, and ultimately make them more engaged with the game - and an engaged and engrossed player is a happy player.

Monday, September 5, 2011

Don't Forget Fun

A while ago I played through Darksiders, a beat-em-up where you play the role of "War", one of the four horsemen of the apocalypse. Now, while the writing most definitely fell into the mediocre category, the game on the whole was quite fun. However, there were design aspects that meant the game fell far short of what it could have been.

Part of the problem with Darksiders is that it cobbles together a whole bunch of ideas from different games. Platforming and puzzles have become standards in the modern beat-em-up, and the Prince of Persia series was great for mixing these aspects together with beat-em-up combat. Darksiders does okay in this regard, but its shortcoming is that the game is schizophrenic in its presentation and design. You have completely new abilities and mechanics dumped upon you as the game progresses, but few of these mesh well together. You get a gun, then a horse, then a grappling hook, then a portal gun, then "see invisible" mask, and a few other goodies besides. All these things might be interesting in their own regard, but they simply don't work well together and force you to engage with new mechanics which are used for a period and then largely abandoned.

Worse still, some of these mechanics become tedious. Playing portal in Darksiders for the most part requires little thought or puzzle solving, for all the portal locations are predetermined, leaving the player with few possible options to solve a problem. Worse, the game counter-intuitively has the mechanic such that it is possible to shoot a new portal through an existing portal, yet at no point is this actually explained to the player, which resulted in many players engaging in intentional suicide/respawn patterns in order to establish a portal in what seemed like an otherwise unreachable location. Movement mechanics and particularly the "see invisible" mechanic led to backtracking that added very little to the game except extended playtime.

This was one of the contributing factors to the game's main problem: it stopped being fun. The backtracking of the game meant players were going over old territory repeatedly, but even worse, they were dealing with enemies that became increasingly less fun to fight. This was through the introduction of single enemies that could deal a large amounts of damage and required a largely defensive strategy in order to defeat. Considering much of the fun of the combat of the game (as with many/most beat-em-ups) is the challenge and skill involved with stringing together combos in order to defeat a large group of enemies. Staged boss fights are the icing on the cake, but the bread and butter is the defeat of enemy hordes - a recipe that the Dynasty Warrior series understands implicitly, as that is the entire point of the game.

As the game progressed, the introduction of enemies such as Wraiths, Grappleclaws and Undead Shield Lords forced the player into more defensive fighting strategies, undermining the fun of the fighting activities the player had experienced early in the game. As Darksiders continued, its combat became less fun, and its gameplay more repetitive. Darksiders is one of those rare cases where it would have been much better if the game had ended half a dozen hours earlier. A shorter game would have cut out the additional repetition introduced by the tail end, not to mention the more tedious fighting sequences in the game. While it's an enjoyable romp, Darksiders will ultimately leave you feeling a bit irritated by the time you reach the end because of these shortcomings, and the fact that the boss fights become progressively easier until the fight battle feels wholeheartedly underwhelming.

The take home lesson from Darksiders is to not forget what makes your game fun. Good design is not about trying to pack as many different mechanics into a single game as possible, even if you're taking them from games that are very popular. It's not about making the game as long as possible if it's at the expense of the quality of the gameplay

Focus on one gameplay mechanic within a game (probably three at most) and make sure it is fun and has depth in order to make your game as enjoyable as possible. Try to make a gameplay mechanic easy to pick up, but difficult to master. Make it possible for the player to succeed, but if they wish to succeed at a higher degree of difficulty or earn some recognition of increased skill from the game (e.g. via a points system), they will have to learn and practice mastering the mechanic.

Make your primary mechanic fun and make sure the player can enjoy it for the entire length of the game, and you will have avoided the mistake that Darksiders makes.

Part of the problem with Darksiders is that it cobbles together a whole bunch of ideas from different games. Platforming and puzzles have become standards in the modern beat-em-up, and the Prince of Persia series was great for mixing these aspects together with beat-em-up combat. Darksiders does okay in this regard, but its shortcoming is that the game is schizophrenic in its presentation and design. You have completely new abilities and mechanics dumped upon you as the game progresses, but few of these mesh well together. You get a gun, then a horse, then a grappling hook, then a portal gun, then "see invisible" mask, and a few other goodies besides. All these things might be interesting in their own regard, but they simply don't work well together and force you to engage with new mechanics which are used for a period and then largely abandoned.

Copying portal was out of place, and generally not a good idea

Worse still, some of these mechanics become tedious. Playing portal in Darksiders for the most part requires little thought or puzzle solving, for all the portal locations are predetermined, leaving the player with few possible options to solve a problem. Worse, the game counter-intuitively has the mechanic such that it is possible to shoot a new portal through an existing portal, yet at no point is this actually explained to the player, which resulted in many players engaging in intentional suicide/respawn patterns in order to establish a portal in what seemed like an otherwise unreachable location. Movement mechanics and particularly the "see invisible" mechanic led to backtracking that added very little to the game except extended playtime.

Players should not need to come to the same location over and over again

This was one of the contributing factors to the game's main problem: it stopped being fun. The backtracking of the game meant players were going over old territory repeatedly, but even worse, they were dealing with enemies that became increasingly less fun to fight. This was through the introduction of single enemies that could deal a large amounts of damage and required a largely defensive strategy in order to defeat. Considering much of the fun of the combat of the game (as with many/most beat-em-ups) is the challenge and skill involved with stringing together combos in order to defeat a large group of enemies. Staged boss fights are the icing on the cake, but the bread and butter is the defeat of enemy hordes - a recipe that the Dynasty Warrior series understands implicitly, as that is the entire point of the game.

As the game progressed, the introduction of enemies such as Wraiths, Grappleclaws and Undead Shield Lords forced the player into more defensive fighting strategies, undermining the fun of the fighting activities the player had experienced early in the game. As Darksiders continued, its combat became less fun, and its gameplay more repetitive. Darksiders is one of those rare cases where it would have been much better if the game had ended half a dozen hours earlier. A shorter game would have cut out the additional repetition introduced by the tail end, not to mention the more tedious fighting sequences in the game. While it's an enjoyable romp, Darksiders will ultimately leave you feeling a bit irritated by the time you reach the end because of these shortcomings, and the fact that the boss fights become progressively easier until the fight battle feels wholeheartedly underwhelming.

These were dull and annoying to fight

The take home lesson from Darksiders is to not forget what makes your game fun. Good design is not about trying to pack as many different mechanics into a single game as possible, even if you're taking them from games that are very popular. It's not about making the game as long as possible if it's at the expense of the quality of the gameplay

Focus on one gameplay mechanic within a game (probably three at most) and make sure it is fun and has depth in order to make your game as enjoyable as possible. Try to make a gameplay mechanic easy to pick up, but difficult to master. Make it possible for the player to succeed, but if they wish to succeed at a higher degree of difficulty or earn some recognition of increased skill from the game (e.g. via a points system), they will have to learn and practice mastering the mechanic.

Make your primary mechanic fun and make sure the player can enjoy it for the entire length of the game, and you will have avoided the mistake that Darksiders makes.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)